The Metropolitan Transportation Authority is at it again.

The agency, which has faced criticism for its arbitrary rejection of ads featuring sexual products geared toward women while letting those marketed to men grace transit around the city, is once more making headlines for a recent refusal.

This time the company it denied is suing. And we hope they win.

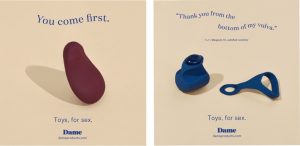

By all accounts, Dame Products, a women-focused company that sells sex toys, did everything right in trying to get its ads on MTA transit. It worked side-by-side with MTA ad contractor Outfront Media to conceptualize its ads. It made the adjustments suggested by Outfront. It used images of vibrators, yes, but they’re disguised somewhat by their unexpected, decidedly non-phallic shapes.

By all accounts, Dame Products, a women-focused company that sells sex toys, did everything right in trying to get its ads on MTA transit. It worked side-by-side with MTA ad contractor Outfront Media to conceptualize its ads. It made the adjustments suggested by Outfront. It used images of vibrators, yes, but they’re disguised somewhat by their unexpected, decidedly non-phallic shapes.

In December, the MTA rejected ads submitted by Dame Products because the ads promoted a “sexually oriented business.”

Never mind that the MTA has accepted ads from a business that sells erectile dysfunction medication, which uses the none-too-subtle imagery of a cactus. (Gee, what could that be “suggesting?”)

Dame Products is understandably pissed. It poured $150,000 into developing this campaign, and it consulted just the way it should have to ensure the campaign would be accepted by the MTA. Call it a case of getting strung along.

“The MTA could have just said no from the beginning,” Alexandra Fine, CEO and co-founder of Dame Products, told us.

Last month, her company filed a lawsuit against the agency, alleging the MTA violated free speech protections by rejecting the ads. The suit also cites inconsistencies in MTA policies.

“We decided to file the lawsuit when we realized legal action can be effective in closing the pleasure gap along with actually selling our products,” Fine says. “They go hand in hand.”

It’s not the first time the agency has come under fire for this type of case or this type of apparent discrimination. In spring 2018, the MTA rejected ads for Unbound, another company focused on female sexual health (that also sells sex toys).

In one of the ads deemed too sexual, a woman lounges on her bed, sitting next to a table that displays, among other things, a vibrator and another sex toy. They aren’t the focal points of the visual, though — it’s stuffed with images of other things, like an old-fashioned telephone, a really skinny cat and Tiki-themed knickknacks.

Following a public outcry over the rejection, the MTA and Outfront pledged to work with Unbound on compromise imagery. But the compromise never emerged. Unbound CEO Polly Rodriguez later told CNN the agency demanded removal of phallic imagery, which Rodriguez felt was a double standard.

Following a public outcry over the rejection, the MTA and Outfront pledged to work with Unbound on compromise imagery. But the compromise never emerged. Unbound CEO Polly Rodriguez later told CNN the agency demanded removal of phallic imagery, which Rodriguez felt was a double standard.

She noted the ED products the MTA allowed to be advertised and said its enforcement of rules related to “sexually oriented businesses” indicated there are two standards for products, depending on who they’re marketed to.

“Male sexuality can be visible and is deemed a health issue — and women’s health is not to be seen in public, it’s not to be visible. It’s a really toxic narrative for us to have as a culture,” Rodriguez told CNN Business.

She makes solid points. And the MTA has an inconsistent history on what it accepts and rejects. It’s not just about sex, but it clearly is about women. Four years ago, the MTA rejected ads for period-conscious underwear company THINX for including, gasp, the word “period” in its copy.

The point is not that the MTA is a bunch of prudes, though that may be entirely true.

Here’s the issue. The MTA has too much power in the New York City outdoor space, and it wields that power randomly. We’re tired of seeing situations like this, where the agency can’t give a good reason for its decision, let alone defend the logic behind it. (We suspect because there isn’t any.)

Good advertising pushes the envelope. It makes people think about things in a new way, grabbing their attention and keeping it.

Great advertising elevates message to art form. Subways provide a captive audience for the delivery of this advertising. The MTA vastly underestimates the sophistication and intelligence of this audience.

Look around. We’ve got billboards advertising marijuana on every corner in Los Angeles — and nobody bats an eye. The MTA seems to exercise its veto power sometimes just because it can. That’s no way to make policy and certainly explains some of the problems dogging the agency right now.

The MTA is in the midst of a vaguely promised “restructuring,” to take place this summer. That’s undoubtedly sparked by dire financial issues that have threatened to derail the transit agency.

Already-poor conditions on the city’s buses, subways and commuter lines have deteriorated. Many commuters and students have sought other forms of transportation to avoid dealing with issues such as aging infrastructure and rising costs of maintaining its fleet of vehicles.

A recent report predicts that the MTA will be $42 billion in debt by 2022. Ironic, huh—in light of that, you’d think the service could use every penny of advertising anyone wants to throw its way.

The MTA needs to modify — and modernize — its stance on what type of advertising it accepts. Exerting power just because you can is a poor reason to turn down advertising.

Guidelines are written for a reason. Leaving those guidelines open to such wide swings in interpretation (how can you argue ED drugs are any more “suggestive” than period pants—the latter doesn’t even have anything to do with sex) just makes the MTA look silly.

Agencies such as the MTA owe those who support it, the advertisers, a transparent and well-thought-out advertising policy that amounts to more than throwing darts at a board. If we don’t know what types of ads are “acceptable,” we spend way too much time and money trying to please capricious officials who tell us different things depending on the time of day or direction of the wind or how long the line is at TKTS.

This waters down messages and decreases the efficiency of advertising. And, irony alert No. 2, this will make fewer companies want to advertise with the MTA.

It’s time for someone to hold the MTA accountable, and we’re glad Dame Products is trying to do it. We need to hear more voices from the OOH community calling behavior like this what it is—unproductive, unprofessional and unlikely to result in productive relationships, which is critical to producing successful advertising.